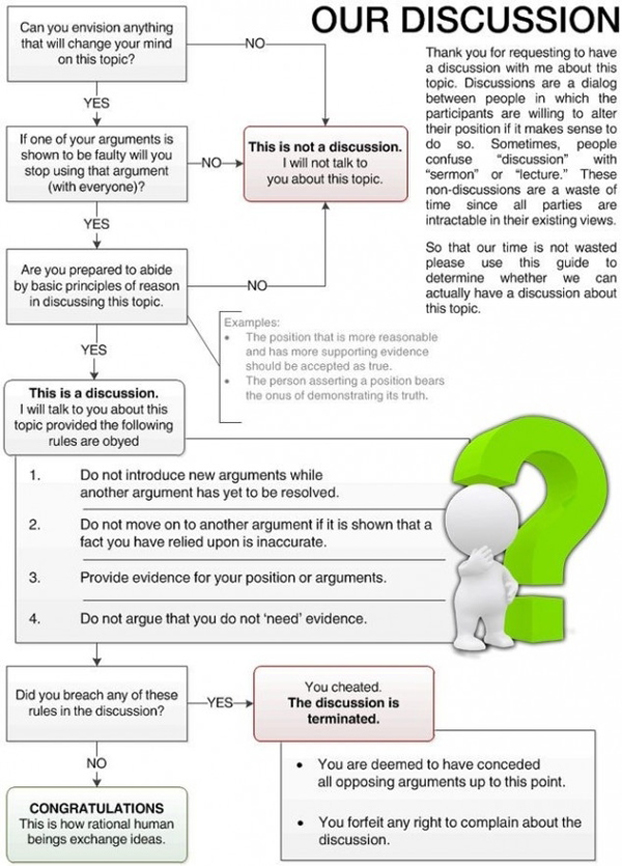

One thing I'm always wrestling with is what it means to be in right relationship-to deal with difficult issues well, to honor the different ideas, decisions, and understandings we all have, while still having a perspective and a commitment of your own.

That is why I've gotten trained in Mediation from the Kansas Institute of Peace and Conflict Resolution and in the Circle process with the Saint Louis area Restorative Justice Collaboration . It is in the spirit of restorative justice and good human relationships that I present this graphic (click to enlarge):

thought catologue

which I found today.

In particular, I think it is really important to be willing to change one's mind based on the evidence, and to listen for your own bad arguments.

I think this is a limited graphic of course-there are other kinds of conversations, that don't involve argument. We can tell stories, exchange experiences, confess, commiserate, and teach, but it is important, I think, to know the ethics of conversation, and that a debate with entrenched positions is usually useful only as public spectacle, rather than the parties involved.

Wednesday, March 23, 2011

Monday, March 7, 2011

perverse incentives

I learned something, and I thought I’d share it with the world.

You know how many coaches, bosses, parents, etc. think it is a good idea to yell at people to motivate them? Here's the classic angry coach clip:

This always bugs me, because I think its bad to yell at people (meanness is part of my moral calculation, even if there is room for calling people brood of vipers and white washed tombs, biblically speaking, and even if I have been known to practice a touch of sarcasm myself).

Also, it is questionable behavior because there is some pretty good social science evidence from a number of fields that yelling doesn’t work-that praise is a better motivator. I’m most versed in the theory in regards to children, I understand it is pretty true everywhere.

So why do so many people think yelling is good idea? Well, here is one theory:

To summarize:

the writer, Daniel Kahneman was training flight instructors, and one defended his behavior like this:

He said, “On many occasions I have praised flight cadets for clean execution of some aerobatic maneuver, and in general when they try it again, they do worse. On the other hand, I have often screamed at cadets for bad execution, and in general they do better the next time. So please don’t tell us that reinforcement works and punishment does not, because the opposite is the case.”

Daniel thought fast:

I immediately arranged a demonstration in which each participant tossed two coins at a target behind his back, without any feedback. We measured the distances from the target and could see that those who had done best the first time had mostly deteriorated on their second try, and vice versa.

In short: whatever you do to motivate someone, if they are performing badly, they'll likely do better next time. If they perform well, they're equally likely to perform worse next time. Thus, with any reasonably motivated group of people, they will do better every time you yell at them, and they will do worse every time you praise them, because you praise when they succeed and yell when they fail. But if you switched your management behavior, yelling at them when they succeeded or praised them when they failed, the same phenomenon would occur in reverse. If you actually want to improve their performance the most (not to mention be a better person) then you will use a positive reinforcement technique rather than a punitive one.

Sadly understanding of how to motivate people is so deeply ingrained that its going to be really hard to break coaches, teachers, and managers of this practice.

So, just so you know, you’re great- I’m impressed with the work you’re doing, and the way that you've improved over time, and I’m glad that you’re trying hard, even when you make mistakes.

Tuesday, March 1, 2011

What we produce

A congregant shared this article from Wired magazine with me today:

1 Million workers

it is a reflection on the Foxconn plant in Shenzhen, China, a plant that employs over a million people, is the source of many Apple products, and was in the news recently because a rash of worker suicides.

It explores factory conditions in China, and asks difficult questions-what are safe, healthy, and proper working conditions in a country with as much poverty as China? How does our consumption in the west shape the rest of the world? What does it mean to live at our resource level?

Two quotes I found particularly meaningful:

"By many accounts, those unskilled laborers who get jobs at Foxconn are the luckiest. But eyes should absolutely remain on Foxconn, the eyes of media both foreign and domestic, of government inspectors and partner companies. The work may be humane, but rampant overtime is not. We should encourage workers’ rights just as much as we champion economic development. We’ve exported our manufacturing; let’s be sure to export trade unions, too."

"To be soaked in materialism, to directly and indirectly champion it, has also brought guilt. I don’t know if I have a right to the vast quantities of materials and energy I consume in my daily life. Even if I thought I did, I know the planet cannot bear my lifestyle multiplied by 7 billion individuals. I believe this understanding is shared, if only subconsciously, by almost everyone in the Western world.

Every last trifle we touch and consume, right down to the paper on which this magazine is printed or the screen on which it’s displayed, is not only ephemeral but in a real sense irreplaceable. Every consumer good has a cost not borne out by its price but instead falsely bolstered by a vanishing resource economy. We squander millions of years’ worth of stored energy, stored life, from our planet to make not only things that are critical to our survival and comfort but also things that simply satisfy our innate primate desire to possess. It’s this guilt that we attempt to assuage with the hope that our consumerist culture is making life better—for ourselves, of course, but also in some lesser way for those who cannot afford to buy everything we purchase, consume, or own.

When that small appeasement is challenged even slightly, when that thin, taut cord that connects our consumption to the nameless millions who make our lifestyle possible snaps even for a moment, the gulf we find ourselves peering into—a yawning, endless future of emptiness on a squandered planet—becomes too much to bear."

As we reflect as a congregation what it means to live in sustainable ways, this is why we ask the question.

1 Million workers

it is a reflection on the Foxconn plant in Shenzhen, China, a plant that employs over a million people, is the source of many Apple products, and was in the news recently because a rash of worker suicides.

It explores factory conditions in China, and asks difficult questions-what are safe, healthy, and proper working conditions in a country with as much poverty as China? How does our consumption in the west shape the rest of the world? What does it mean to live at our resource level?

Two quotes I found particularly meaningful:

"By many accounts, those unskilled laborers who get jobs at Foxconn are the luckiest. But eyes should absolutely remain on Foxconn, the eyes of media both foreign and domestic, of government inspectors and partner companies. The work may be humane, but rampant overtime is not. We should encourage workers’ rights just as much as we champion economic development. We’ve exported our manufacturing; let’s be sure to export trade unions, too."

"To be soaked in materialism, to directly and indirectly champion it, has also brought guilt. I don’t know if I have a right to the vast quantities of materials and energy I consume in my daily life. Even if I thought I did, I know the planet cannot bear my lifestyle multiplied by 7 billion individuals. I believe this understanding is shared, if only subconsciously, by almost everyone in the Western world.

Every last trifle we touch and consume, right down to the paper on which this magazine is printed or the screen on which it’s displayed, is not only ephemeral but in a real sense irreplaceable. Every consumer good has a cost not borne out by its price but instead falsely bolstered by a vanishing resource economy. We squander millions of years’ worth of stored energy, stored life, from our planet to make not only things that are critical to our survival and comfort but also things that simply satisfy our innate primate desire to possess. It’s this guilt that we attempt to assuage with the hope that our consumerist culture is making life better—for ourselves, of course, but also in some lesser way for those who cannot afford to buy everything we purchase, consume, or own.

When that small appeasement is challenged even slightly, when that thin, taut cord that connects our consumption to the nameless millions who make our lifestyle possible snaps even for a moment, the gulf we find ourselves peering into—a yawning, endless future of emptiness on a squandered planet—becomes too much to bear."

As we reflect as a congregation what it means to live in sustainable ways, this is why we ask the question.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)